📰 Working with the literature: tools and approaches

Summary

- Ref management is a part of PIM: helps to capture, search, manage, and use your collection of sources.

- I use a system based on Zotero as reference manager.

- Key alternatives are JabRef, Mendeley, Refworks, EndNote (there is more).

- Another crucial part is integration with the editor. I use (pure) black magic involving (Space)Emacs (not really beginner-friendly; there are alternatives).

- Keeping notes in a streamlined way is useful. There are several approaches, and several classes of tools – see A note on notes.

- There are several ways to discover new literature, including proactive search in search engines and specialized databases, as well as receiving updates from web feeds, mailing lists, and seminars.

- No universal solutions: find out what works for you.

- Methods, habits, and content are more important than tools.

Corrections, suggestions, and comments are very welcome.

Introduction

Here I am discussing the system supporting my workflow, mentioning some of

alternative options. It may or may not work for you, of course, but hopefully

will provide some inputs to design your own IT “ecosystem”. Here is a very

general (and therefore, useless by itself) description of the relevant

workflow:

This is a large topic, but roughly speaking the system1 has three key components:

- reference manager (works with bibliography data, such as

.bibentries, along with PDF files); - notes (that reflect your thinking process related to this paper/piece of information),

- editor integration(s) (that extracts the information from the other two as you write your manuscript).

It can be organized in many ways (including some good old paper-based versions that were reported to be… very productive, to say the least2; a little more on this below). I had the following specific requirements in mind:

- The system must be future-proof. Research is (hopefully) a long-term endeavor, so lock-in with proprietary technologies is not acceptable. Storing data in plain text is best, open standards and free software are my friends. Oh yes, and I don’t want to store my data in cloud all the time, I love tools that work offline.

- It must do the following things:

- capture a paper from a browser easily, retrieving bibliographical info automatically when possible (including metadata extraction from PDFs).

- manage references efficiently (edit fields, etc.), categorize things, etc.

- play well with LaTeX (mostly, looking for and inserting citations).

- (something that I hope you will ignore:) a large benefit for me had anything that worked well within Emacs.

The core component of such system is, of course, a (bibliography-, citation-, or) reference-manager.

On references and bibliography

Reference managers

A reference-management software is a tool that lets you to (surprise!) manage

references, i.e., bibliographical data: author, title, publisher data, etc.

That is, it captures and stores the bibliographical data in some internal

format (e.g., a .bib file, an SQLite database, etc.), and then can format it

as you’d like: using the chosen citation style and producing outputs in plain

text, word processor document, etc. It also usually helps to generate

bibliographies automatically, so that it updates as you edit the manuscript.

There are several key programs/services out there, and an infinite variety of their comparative analyses:

- Wikipedia has pretty large comparison summary tables. It might be a good place to start, but the number of options is overwhelming.

- Another detailed comparison was made in Technische Universität München.

- University libraries usually have brief overviews of the software they recommend: e.g., a nice one from UCSD, UC Berkeley, U. of Pennsylvania. Also: MiT (specifically on citation management), Harvard, Stanford, U. of Washington,

- There are numerous Reddit discussions (such as: JabRef vs Zotero vs org-ref)

- Of course, there is a paper ivey2018 on the topic3.

Note: it might be important what your colleagues are using. Using the “lab-default” tools might make the choice very simple and efficient.

My personal short list would overlap with the Clemson Library’s one (at the time of writing this):

- Zotero, JabRef - free options (first prio).

- plus Mendeley, Refworks (Clemson guide), EndNote if I allow for commercial products (I have also read some good things about Papers for Mac – but never had a chance to look myself).

This list is not exhaustive, so please refer to more complete resources (including the ones mentioned above) if you’d need. Despite the problem seems somewhat standard from the first sight, different people might want different things, so there is no “universal” solution. Instead of trying to discuss pros and cons, let me just try to sketch what works for me.

My Zotero-based system.

Here is my system in a nutshell, from a technology perspective:

So, basically, I use the following tools:

- Zotero desktop app

- Firefox plugin (“Connector”) to fetch info from the web

- Zotero addons (there is a larger list of these):

- BetterBibTex to make the

.bibrelated magic happen; - LibreOffice integration (think MS Word);

- ZotFile to be able to manipulate PDFs easily, including sending them to the tablet.

- BetterBibTex to make the

Now, the “manuscript” part can be implemented, again, in several ways, and the

purpose here is to supercharge your editor to get info from the .bib file. My

Emacs (Spacemacs) handles this for me4.

I have a convenient (fuzzy) search / auto-completion when I insert the keys:

And also I can easily pull out a PDF or my notes when I need to:

For these rare cases when I use MS Word-like environments, there are LibreOffice and Google Docs integration:

(It is also worth noting that you can just find a paper in Zotero and copy a citation in the necessary citation style, e.g., as a plain text – to insert it anywhere.)

If you find it interesting, there are many demos and tutorials on Zotero on YouTube and other places. Most probably, including a dedicated training in your university library – at CU we have Clemson Libraries trainings/events, including “Zotero for Citation Management”.

Finally, Emacs still feels very DIY-ish, to me. Good if you like to tinker with it, but if I were to look for alternatives – I would start with other popular “mega-editors”, such as VSCode (-ium) or Atom. There must be plugins for this (though, I have never tried these).

A word on LaTeX ecosystem.

I was somehow confused with the LaTeX-related systems, and found a relevant

TeX.StackExchange question. In a nutshell:

As far as I understand, one of the ideas behind biblatex was to move away from

a separate style definition language, BST (see also a manual on BibTeX). While

the SE question mentioned above helped my understanding, but I believe this

topic is better suited for another day. Eventually, everything is determined by

the journal – style description format they provide.

A note on notes.

This is, actually, a separate topic. But if you feel the necessity to take notes on your research in general (like an extended lab journal), there are many options.

Basically, we are talking about a collection of interlinked notes. There are several relevant “keywords” out there that I would like to mention.

- First, one might take a technological perspective and look for software that allows to manage notes. This is, of course, good old Evernote5, and newer, free and open source Joplin.

- There is a vast variety of wiki software (such as DokuWiki or MediaWiki, just to name a couple. But the list is huge.) Some of them are specifically positioned as a Personal Wiki (e.g., such as TiddlyWiki – see a nice 2.5 minutes intro video).

- There are specific solutions for working with an interconnected grid of

“evergreen” notes, the ones you might edit every time when you visit

them. I would like to mention:

- Roam. It looks totally exciting, but web-based (which is a big no-go for me);

- Obsidian. Comparable thing, uses local storage, as far as I can tell. Ironically, I am not sure how good is it with citations/references 😀. Never used it at all, but to me, it looks very promising (especially if it indeed keeps your information in markdown, which is essentially plain text, so you can open it in future no matter what).

- Org-roam. This is a part of Emacs ecosystem over the all-mighty6 orgmode. Free and open source, local solution. This is what I use currently.

- Then, there is a specific method of taking such notes called Zettelkasten.

The word means a slip-box with notes. The idea is that after some time you

actually build such an “external brain” that conversations with it become

surprisingly productive (resulting in new connections and ideas). It can be

implemented with any reasonable tool. In fact, one of the most famous

Zettelkästen was implemented as a wooden box with drawers, filled with

small (paper) notes. It is worth noting: its author, Niklas Luhmann, was

doing Sociology, and this approach might (or might not) be less effective

for math-heavy fields. Anyways: It seems to be a vast topic, and there is a

lot of resources out there, if you are interested further, including7:

- 📖 A book:“How to Take Smart Notes…" by Sönke Ahrens. Despite it has the sort of title I dislike very much, I found the book pretty useful and informative8.

- 💬 A community: r/Zettelkasten on Reddit (the linked note includes couple of good links on the subject; and there is a community wiki, hosted separately)

- On the contrary, someone from my friends just work on a relatively small

number of notes in

.texformat (something like “internal papers” in his lab).

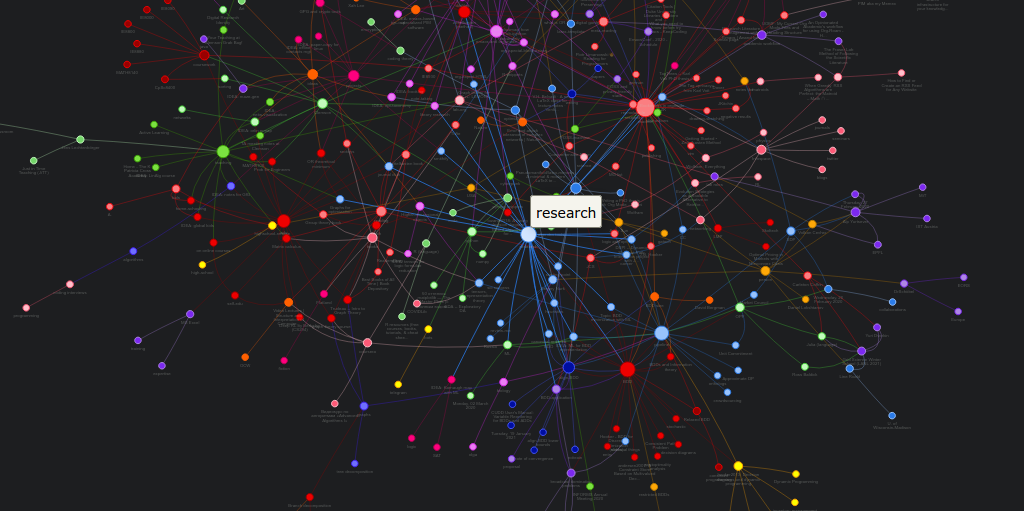

My system basically represents a graph of connected notes. It can even be visualized like this:

Of course, I use it mostly from the text interface – imagine easily editable,

local Wikipedia. Also seems very useful to store code snippets – for saving

useful command line recipes, boilerplate ggplot code for figures, etc.

As a concluding note: it seems to me that specific tools are not as important as discipline, habits and procedures we set up for ourselves. Of course, a lab notebook in one form or another is a must. I liked a point that came up in one of private conversations recently, that notes is your product when you are not working on a specific paper. And when you accumulate enough of them – all this can “graduate” to a paper. Which is surprisingly along the lines of what Dr. Luhmann was saying.

Discovering the literature

I wanted to jot down a couple of words on discovering the literature. Like, where do papers new can come from.

Note: your library might provide a surprising amount of useful resources! E.g., Clemson University Libraries offer “Research & Course Guides” (with/ specific sections on Industrial Engineering, Mathematics, and Computer Science). I would like to thank our Librarian Jennifer Groff for a very productive email conversation, which helped me a lot in preparing this discussion. There might be more useful sources – check out the website!

🔎 Proactive search

Who doesn’t know about free search? Right, right… But still:

- Just Google search is (un)surprisingly good, sometimes.

- Google.Scholar is handy when you are specifically looking for research

papers. (It also provides citation data along the way.) What is more

important: having a paper

X, it allows to make more complicated requests, e.g., find all the papers that citeX, find new papers by keywords among those citingX, and such things. - There are specialized (commercial, usually subscription-based) resources/databases to search for papers: the most general ones are, perhaps, (Elsevier’s) Scopus and (Clarivate’s) Web of Science. Also, there is MathSciNet, EngineeringVillage, etc. Of course, there is more – these are just random examples. I use these for more complicated searches, sometimes.

- (surprise!) The University Library. For example, Clemson Libraries has

subscriptions to many databases, and allows to (1) search across these, and

(2) retrieve paywalled papers. So, I found this “everything” library search

pretty useful. I think our CU library has access to more than 500

databases; to give a random sample:

- SAGE Research Methods

- CREDO reference (search in encyclopedias, dictionaries, etc.)

- ProQuest Disserations and Theses Global

- as a separate note: if you are a CU student, note that Clemson Libraries provide trainings on what is out there and how to use it: e.g., see “Introducing Library Research Strategies and Navigating the Clemson Libraries” from Grad360 – seems to be scheduled for .

Now, that was proactive search. There are also more or less obvious methods to receive papers, well, automatically. Apart from the obvious Twitter (or whatever other social networks are used in your subfield’s community) these are feeds, mailing lists, and various seminars / events.

📰 Feeds: RSS, atom

The idea is that instead of checking relevant websites frequently yourself, you delegate this task to the computer (we’re engineers, after all, right?). There is a web standard for “feeds”, making websites machine readable – so that a special program, feed reader, or a feed aggregator checks out the websites that support such technology, and lets you know if a new paper / blog post / web page on the site was published. As simple as that. A couple of notes here:

- Speaking about software, I would mention Mozilla Thunderbird or Elfeed (if you are into Emacs ecosystem) – this is what I tried to use, but I don’t really have an overview, so can’t comment. Chances are, your default desktop email client (if you happen to use it), or a browser (Safari?) also can do that. Of course, there is a huge comparison table on Wiki. There are web solutions (e.g., Feedly), which I have no clue about. The colleagues pointed out that Zotero can read feeds as well (so you could have everything in one place).

- Now, for this to work it must be supported by the website. There are some solutions that try to circumvent this and try to build an RSS feed for you (see Feed43)

- Some journals provide RSS/Atom feeds: e.g., IJOC, EJOR, OPRE, etc.

- Preprint servers might have feeds – e.g., arXiv mentions subjects feeds, updated daily. (unfortunately, to the best of my knowledge Optimization Online does not do this).

📨 Mailing lists

- Web of Science, Engineering Village, Google Scholar (and, perhaps, many others) allow to set up citation alerts (e.g., weekly/monthly notifications on your search results; alerts for new publications from a specific author, etc.)

- Some journals offer email subscriptions instead of feeds, sending out list of papers, abstracts, etc. (e.g., Mathematical Programming)

- There might be other mailing lists worth mentioning (seminars, departmental lists, etc. – please let me know if you think I missed something worth mentioning separately).

💬 Journal clubs / seminars

- Quite often there are efforts to read and share relevant papers in the “local” community. I know at least one relatively large lab that systematically keeps track of many relevant journals and present “fresh” papers during a regular (internal) event.

- There are also studies-focused reading clubs, aimed mostly not to keep

track of cutting-edge research, but to learn

- how to do good science (essentially, pose and answer good research questions, plan the research, etc.)

- how to write good papers out of it.

- We might want to make one, but this is a topic for another day.

Bibliography

[ivey2018] Ivey & Crum, Choosing the Right Citation Management Tool: Endnote, Mendeley, Refworks, or Zotero, Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA, 106(3), 399-403 (2018). doi. ↩

-

Which is by the way a part of something that is usually called Personal Information Management (PIM) or Personal Knowledge Management (PKM) systems. These two do not seem well-defined concepts, in my opinion, but do have something to do with very important topics, especially for a researcher. ↩︎

-

This is in Sociology – but I believe the benefits should translate well to STEM, at least to some extent. ↩︎

-

Needless to say, this citation was inserted here using Zotero in under 1 minute (and I have a downloaded PDF as a by-product). ↩︎

-

I use layers:

bibtex, pdf, andorg-roam+org-roam-bibtexalong withhelmand such (a mandatory link to my dotfiles). If you are into Emacs world, you might find it useful to watch this EmacsConf2020 talk by Noorah Alhasan, which discusses a very similar approach. ↩︎ -

which I do not like as it is too much cloud-based and not, um… hacker friendly, to my feelings. For example, I do not quite understand how to export my stuff quickly and without losses, should I happen to need this… ↩︎

-

Speaking about orgmode: you can check out this great Bernt Hansen’s page to see what’s possible. But despite I like this technology a lot, I must admit it is still a DIY type of thing, to my taste ↩︎

-

There is also an original paper by Luhmann, “Kommunikation mit Zettelkästen” – however, it is in German 🇩🇪, I haven’t seen any translation. ↩︎

-

It left me with the same kind of feeling as the brilliant “Deep work” by Cal Newport. ↩︎